A Function-Infused and Synthesis-Friendly Vocabulary

In this work, we introduce a chemical vocabulary built from synthesis-friendly building blocks. This vocabulary is designed to support automated, step-by-step assembly of molecules—making the synthesis process faster and more reliable.

These building blocks aren’t just random pieces; they are chemically meaningful units closely tied to important molecular functions. For example, certain blocks might help a molecule bind to a protein target, influence enzyme activity, or interact with metabolic pathways. By working at this functional level, our model can quickly propose new molecules, automate their synthesis, and generate useful functional data as needed.

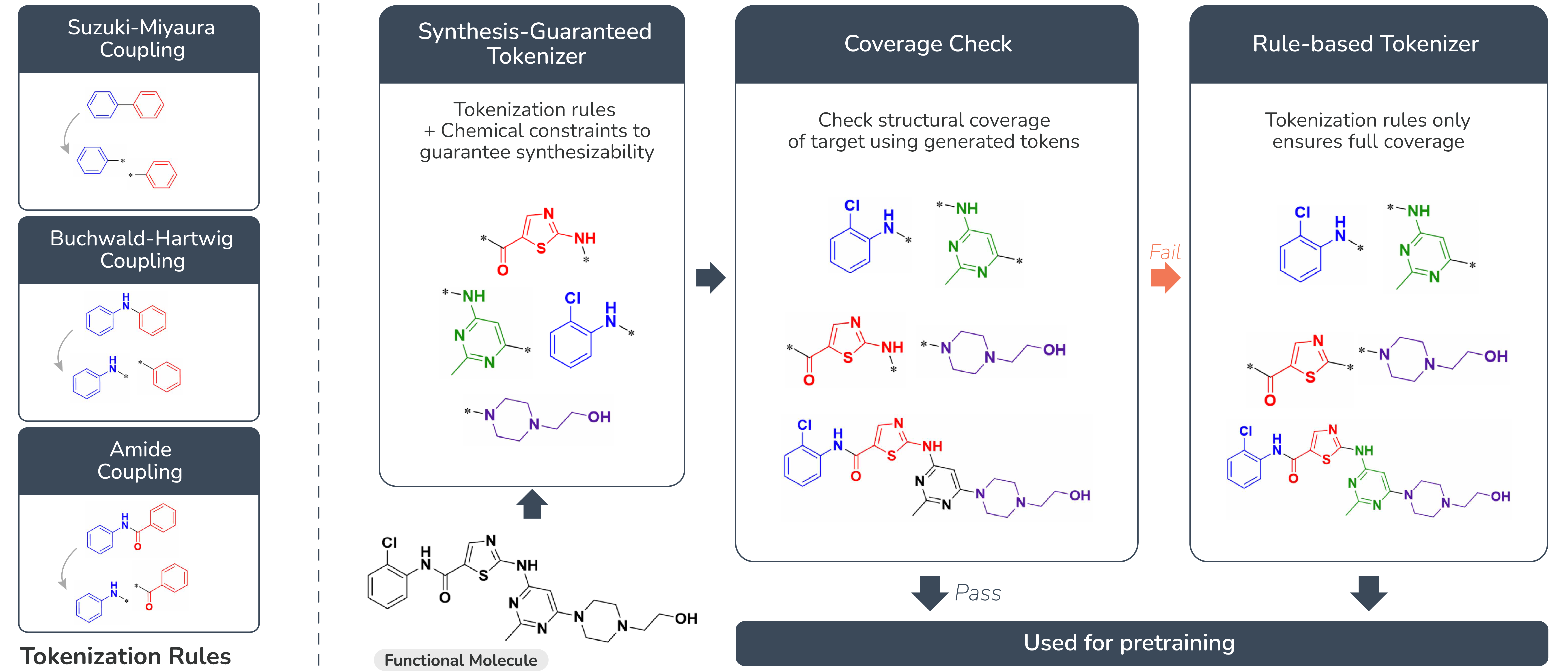

Unlike traditional SMILES strings—which turn molecules into linear sequences but sometimes break important chemical connections—our vocabulary reflects the real, physical layout of molecules. This means that the representation preserves how building blocks are actually connected in space, allowing for more natural and accurate molecule design. In short, this function-infused, synthesis-friendly vocabulary enables rapid, practical, and meaningful molecular discovery. The figure below illustrates how our tokenization method works.

Chemical-Language Modeling

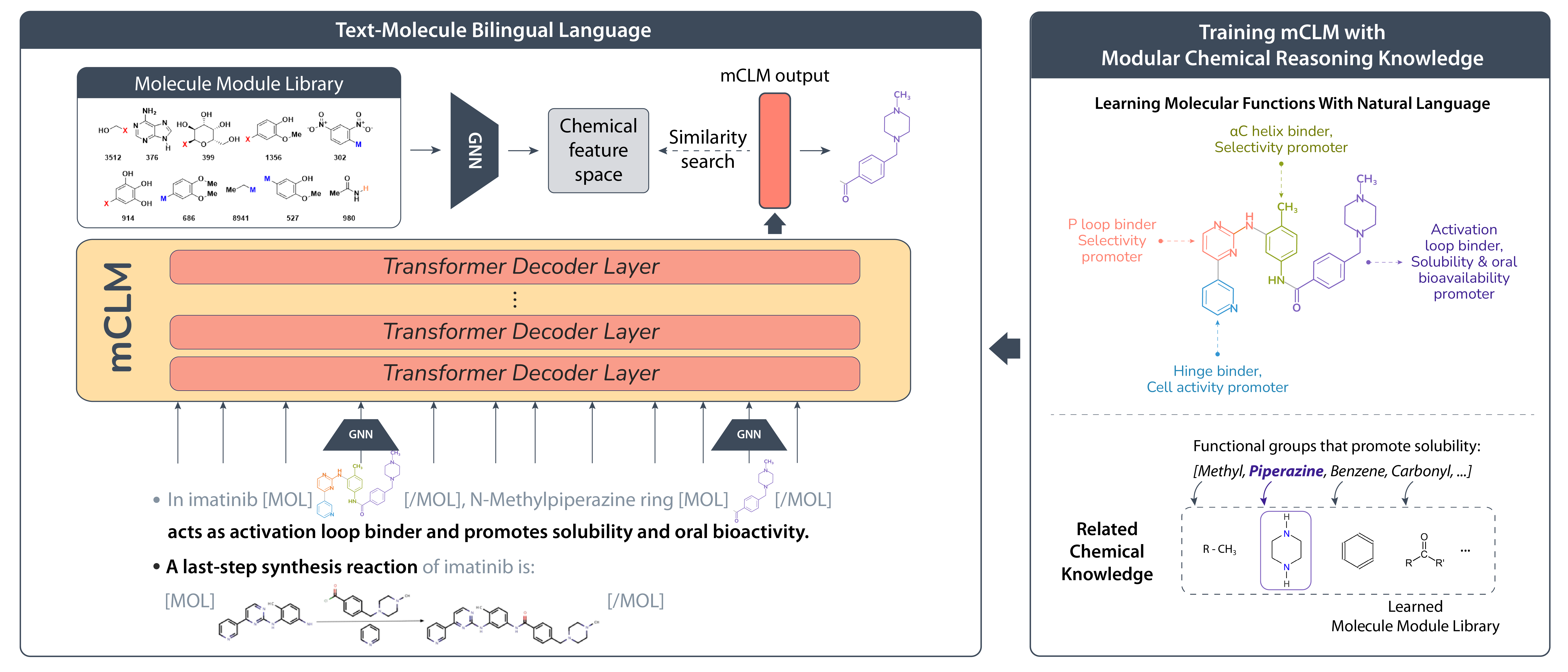

The figure below illustrates the architecture of mCLM, our multimodal Chemical-Language Model. This sequential generative model processes both molecular and natural language sequences in a unified framework. At its core, mCLM leverages the Transformer architecture, which excels at handling sequential data and allows us to build on powerful pre-trained language models as a backbone.

After tokenizing molecules using the method described earlier, each molecular building block is encoded through graph neural networks (GNNs). These molecular representations are then seamlessly integrated with natural language embeddings at positions corresponding to molecule entity names. This creates a “code-switched” language that effectively blends molecular structures with their textual descriptions.

The combined feature sequence is fed into a Transformer decoder-only architecture, which predicts the next token based on all previously generated tokens. This setup enables pre-training on large, multimodal datasets, allowing the model to learn rich relationships between molecular structures and natural language. To maximize efficiency, mCLM is fine-tuned on top of open-source large language models pre-trained on general-domain text corpora. This approach leverages existing linguistic knowledge without the heavy computational burden of training from scratch.

Our training objective employs a unified categorical cross-entropy loss that jointly optimizes for both natural language tokens and molecular building blocks. Formally, the loss compares the true token distribution with the model’s predicted distribution over a shared vocabulary of words and molecular fragments. For natural language tokens, embeddings are directly sourced from the pre-trained language model. For molecular building blocks, embeddings are generated by passing their graph representations through GNNs, followed by a linear adapter that projects them into the same embedding space. This joint training mechanism enables mCLM to fluently “speak” the combined language of chemistry and natural language, bridging the gap between molecular structure and textual description in a single, elegant model.

Critical Chemical Reasoning

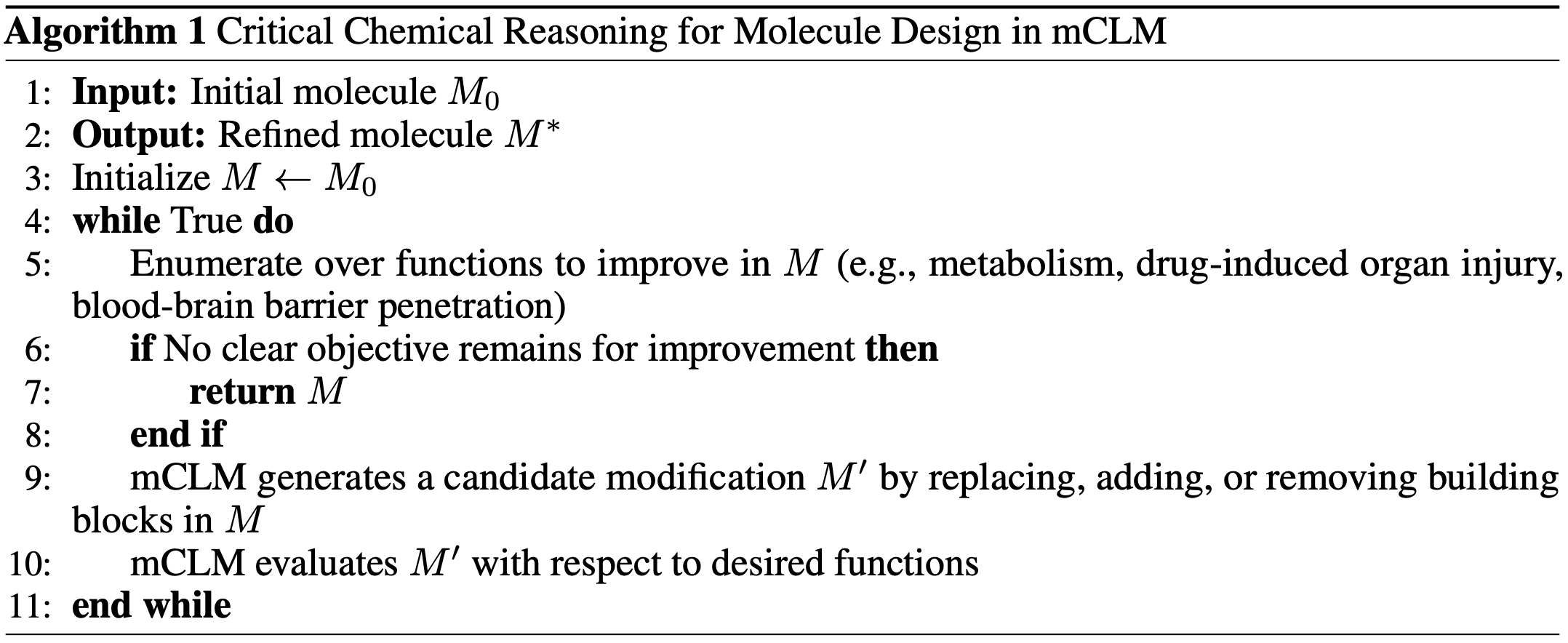

Designing a good molecule isn’t just about getting one property right—it’s about balancing many, often conflicting, chemical functions. Real-world drug design requires optimizing factors like toxicity, bioactivity, and binding affinity all at once. And improving one function can often hurt another. For instance, a molecule with strong potency might also turn out to be highly toxic, making it unsuitable as a drug.

Nature solves this through evolution, gradually refining molecules over billions of years. Inspired by this, we built a reasoning process into our model, mCLM, that allows it to refine its own molecule designs through multiple rounds of improvement.

Here’s how it works: instead of trying to design the perfect molecule in one go, mCLM proposes a version of the molecule, evaluates its functional strengths and weaknesses, and then makes targeted edits to improve it. In each iteration, the model identifies which building blocks still have room for improvement and modifies them with a specific function in mind. This loop continues until either the model reaches a set number of steps or no further meaningful improvements can be made.

Experimental Evaluation

To evaluate how well our model-generated molecules perform, we created oracle models—predictive tools that estimate key drug-like properties. Specifically, we focused on ADMET properties: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity. These are critical to understanding how a molecule might behave in the body. We selected six widely used evaluation tasks from the Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) benchmark:

- AMES: Mutagenicity (whether a molecule might cause genetic mutations)

- BBBP: Blood-brain barrier permeability

- CYP3A4: Inhibition of a key metabolic enzyme

- DILI: Drug-induced liver injury

- HIA: Human intestinal absorption

- PGP: Interaction with a transporter protein involved in drug resistance

We built an ensemble of three models—FARM, ChemBERTA-2, and a GNN—to extract features from molecules and predict their drug-like properties. This gives us a robust way to evaluate how our generated molecules might perform.

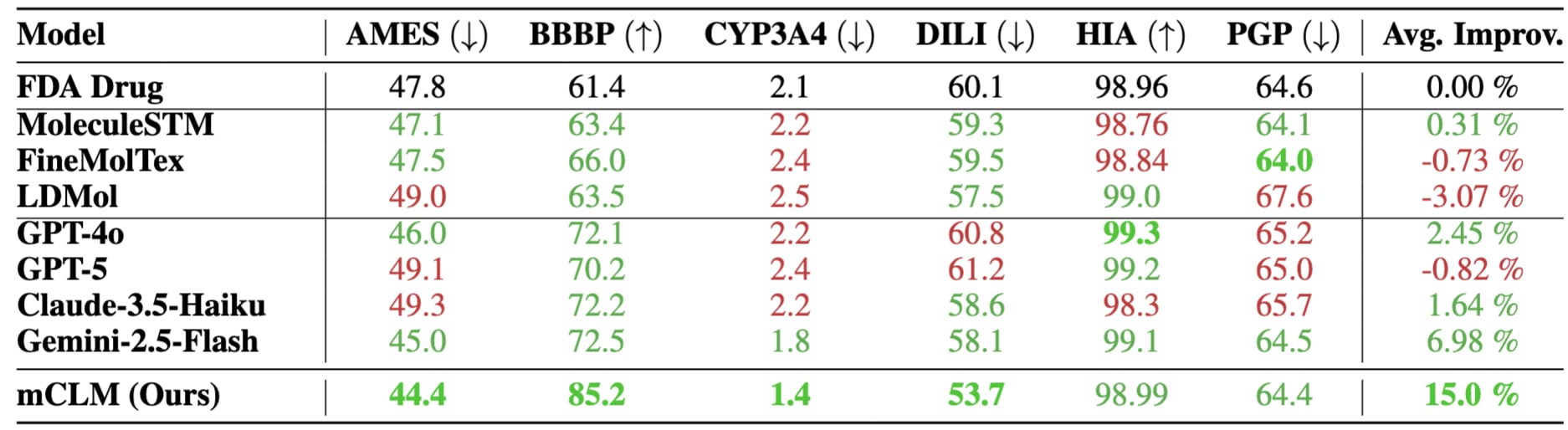

Improving FDA-Approved Drugs with Out-of-Vocabulary Blocks

We tested mCLM on all 430 FDA-approved drugs made of at least 3 building blocks. Most of these molecules (426 out of 430) included blocks the model never saw during training—making this a tough out-of-distribution test. Despite this, mCLM improved 5 out of 6 key drug properties, as shown in the table below. This highlights the model’s ability to generalize and enhance real-world molecules, even with unfamiliar components.

Multi-step Critical Reasoning to Resurrect the “Fallen Angels”

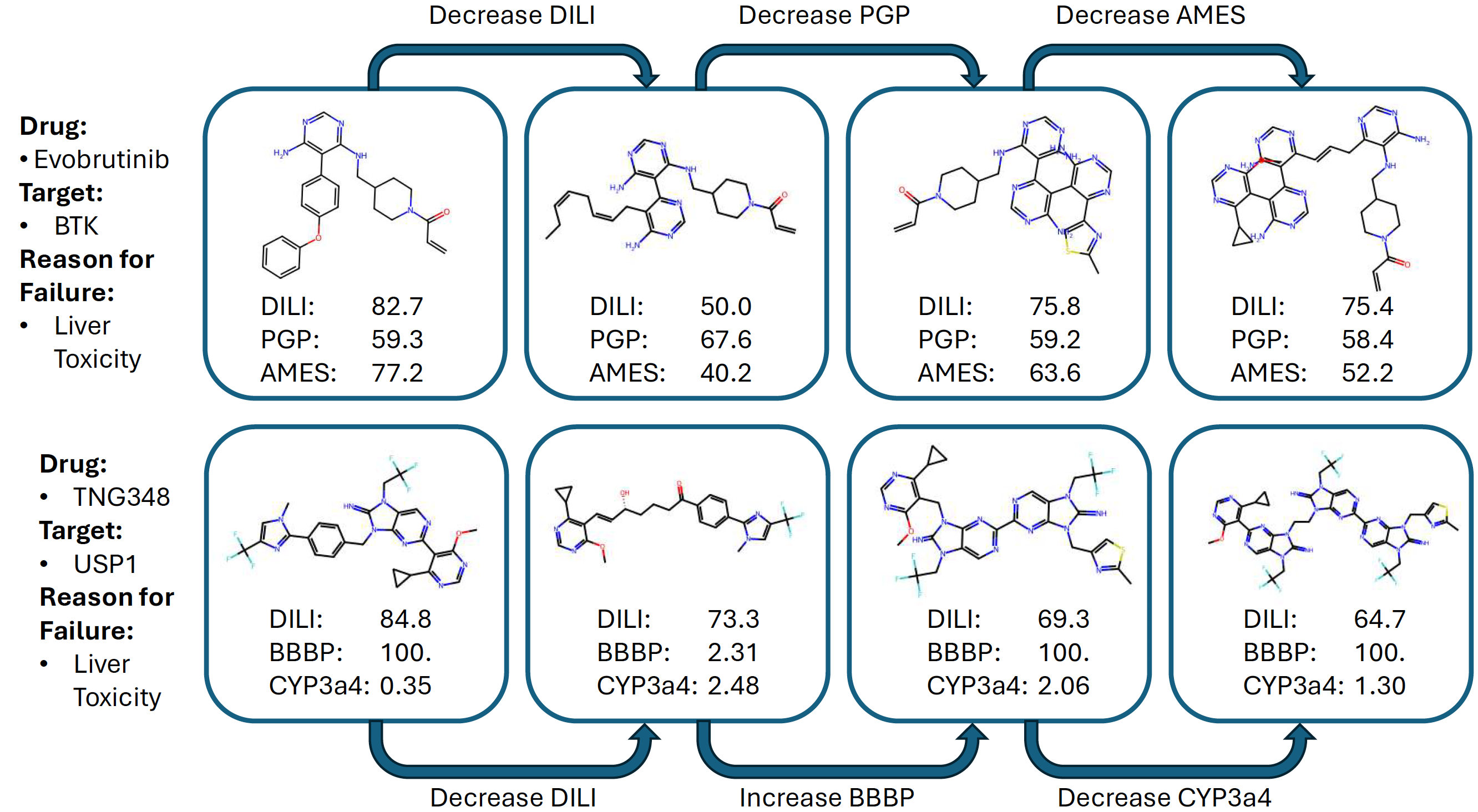

Some drug candidates make it far in development but fail just before FDA approval—often due to a single critical issue. These "fallen angels" still hold great promise because their strengths are known, as are their weaknesses.

Take Evobrutinib, which showed potential for treating multiple sclerosis but was halted due to liver toxicity. Or TNG348, designed to treat BRCA1/2-mutant cancers, but stopped in trials for similar reasons. These molecules represent high-impact opportunities for AI-driven optimization.

Using mCLM, we can apply multi-step functional reasoning to repair these failed drugs. As shown in the figure below, the model first targets the known issue (e.g., liver toxicity), then sequentially improves other affected properties—like PGP for Evobrutinib or BBBP for TNG348. Each change is small, often modifying just one building block at a time, ensuring synthesizability remains intact.

Conclusion

We introduce mCLM, a molecular language model built on a function-infused and synthesis-friendly vocabulary By modularizing molecules into chemically meaningful building blocks and learning with natural language, mCLM enables multi-step functional reasoning to support iterative design, repair, and optimization of small molecules. Its synthesis-friendly vocabulary and compatibility with automated synthesis platforms make it especially suited for scalable, AI-driven molecular design. From generating novel compounds to reviving near-miss drug candidates, mCLM marks a practical and promising step toward truly intelligent molecular discovery.

We plan to release future mCLMs with more features by incorporating 3D molecular structures and physical constraints, enabling deeper understanding of molecular geometry and reactivity. Expanding into protein and nucleic acid sequences will let mCLM reason across biological functions, including protein-ligand interactions and genetic variation.

We'll also explore connections to simulation tools and chemical knowledge bases to enhance its reasoning over reaction dynamics and synthesis pathways. Looking forward, mCLM will engage in multi-agent systems—collaborating with AI agents, human scientists, and automated labs—to design molecules that are both novel and readily synthesizable.

License

This project is licensed under Apache License 2.0. See the LICENSE file for details.

BibTeX

@article{edwards2025mclm,

title={{mCLM}: A Function-Infused and Synthesis-Friendly Modular Chemical Language Model},

author={Carl Edwards, Chi Han, Gawon Lee, Thao Nguyen, Bowen Jin, Chetan Kumar Prasad, Sara Szymkuc, Bartosz A. Grzybowski, Ying Diao, Jiawei Han, Ge Liu, Hao Peng, Martin D. Burke, Heng Ji},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.12565},

year={2025}

}